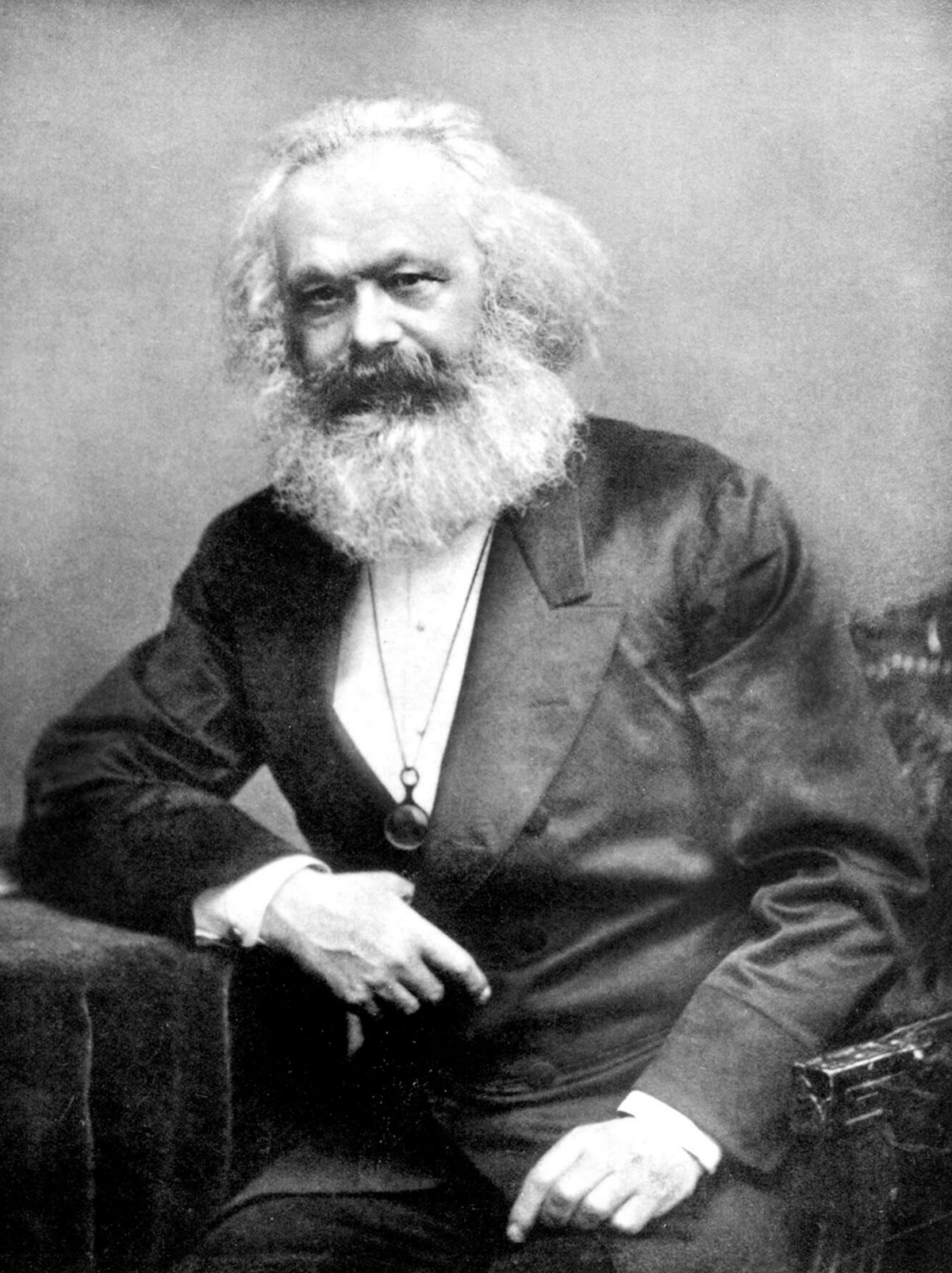

Karl Marx (5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German-born writer, economist, and sociologist, very polarizing to this day, who is known best for writing about, theorizing and advocating the Political Ideologies of socialism and communism.

His best known and proverbial works are The Communist Manifesto (1848), a short pamphlet co-written with Friedrich Engels, in response to a series of revolutions across Europe that year and the Doorstopper that is Capital. Both works are bywords for socialism and communism, but neither was the first work about socialism — it was already a common word by the time it was published, and socialist thought was grounded in some of the more left-wing thinkers of The Enlightenment (which Marx cited as his main influence).

The Communist Manifesto condenses Marx's ideas that history is "a history of class struggle" and that the new capitalist societies of the 19th century, while originally revolutionary (in that they toppled the corrupt aristocracy during The French Revolution and the later wars of reunification in Italy and Germany), led in turn to a new ruling class (labelled the "bourgeoisie"note ) that comprised those who owned capital and means of production that nonetheless functioned on exploitation of the vast majority of workers who did most of the work for little pay, no protection and in deplorable conditions. In the same way that the aristocrats created the bourgeoisie who replaced them as the ruling class, the bourgeoisie will in turn be succeeded and replaced by the newly emergent working class who, in sharp contrast to the ignorant, bonded peasantry of feudalism, was urban and educated (attributes that were necessary for them to work the machines and other tools), organized into labouring units that brought them into contact with workers from other parts of the capitalist nation, leading to the development of a new identity. To Marx, they constituted a new revolutionary class, nurtured in the conditions of the capitalist state. They would become more intelligent as society advances, until the workers had it with their oppression under the class system and set to pave the way for a revolt and the creation of a new socialist society. This would start a lengthy process that would lead first to a society governed directly by the working class (i.e., the dictatorship of the proletariatnote ) but gradually guide it to scientific communism: a global, classless, stateless technological society.note

His social, economic, political, and philosophical views are collectively known as Marxism: a Genre-Busting philosophy that combines historical inquiry, statistical analysis, journalism and philosophy that subsequently influenced nearly all left-wing revolutions and movements since the mid-19th century, and later expanded into fields of humanities, social sciences, linguistics, art, and psychology. For instance, many literary theorists used Marxist ideas to look at literature and culture (film, theatre, opera) in social and historical contexts, resulting in many Alternative Character Interpretations and revivals in the fortune of hitherto neglected works, in addition to his influence on many artists, such as Bertolt Brecht, Sergei Eisenstein, and Jean-Luc Godard.

Despite his reputation as a prophet, with his rhetoric and habit of making visionary predictions not helping his case, Marx's theories about revolutionary practice succeeded contemporary radical events (the Revolutions of 1848, the Paris Commune) rather than anticipating them. They are indeed analytical think pieces about ongoing events and journalistic in character, and Marx used his regular paying job at the New York Herald Tribune's foreign desk to report on various events as and when they happened. The fact that Marx engaged with such political journalism is itself a radical departure from his background as an academic philosopher, and would later provide the model for the philosophe engagé codified by Jean-Paul Sartre. Later writers (mostly, but not exclusively, grounded in analytic philosophy) criticized this stance for calling into question to what degree Marx's ideas and practices are, respectively, carefully developed theories versus instinctual reactions and gut analyses of faraway events that Marx only knew by third hand. This blurring of lines meant that many of Marx's ideas, shaped by the context of the middle of the 19th century, provided an impression of a more coherent and complete view than was actually formulated. In their view, this allowed many 20th-century revolutionaries to claim Marx based on selective interpretation. Vladimir Lenin spearheaded the first successful Marxist revolution in the Russian Empire, and Marx's legacy is to a large extent tied to the fortunes of that event and its highly ambiguous outcomes across the 20th century.note

Marx himself resided in London and analysed the changes in 19th-century England at the height of The British Empire and most of his works analyse Capitalism far more than they prescribe Socialism. During this era, corporations were allowed to do almost anything they wanted and there were no laws which protected workers. Child labor was the rule rather than the exception, no women and only very few men could vote, no laws existed to guarantee safe working conditions, most of the many, many poor had barely enough money to live, and there was no financial safety net protecting people from horrific poverty. It's also worth noting that during his age, the legacy of feudalism was still strong on the Continent, and most of the wealth was controlled by rich families who had possessed it for generations. Inequality and poverty were far worse back then, and the empires of Europe were spreading globally, seeping into cultures like those of India, China, Algeria, Egypt, and many nations in sub-Saharan Africa and South America. It is no coincidence that Marx's ideas had a far stronger influence, and maintains a more positive and/or neutral legacy, in these colonial outposts than in their respective metropoles. This also led Marx, a German exile, to formulate an internationalist post-national outlook to counter the rise of what would now be called globalization. Marx's influence in the Western liberal nations (what is now called the "First World") would be of a subtler, more intellectual nature.note Marx is considered to be one of the founders of modern social sciences, along with Émile Durkheim and Max Weber. Unlike many other philosophers and intellectuals of his time, he insisted that social theories must be examined through a scientific method and direct on-the-ground empirical research of statistical records and figures. His philosophy of historical materialism was the first major case against the "Great Man" view of history of kings, emperors, and popes, and shifted attention to the largely neglected and relegated-to-a-footnote masses in history, paving the way for Annales historians such as Fernand Braudel. As an economist, Marx remains heterodox, and many modern economic institutions reject his work as scientifically incorrect. Nevertheless, Marxist economics retains a significant following and continues to be used as the foundation of socialist economic ideology.

Many later historians argue that Marx's key political influence came via indirectly promoting reform in many liberal nations, many of them intended to co-opt the thunder of radical movements. This assertion is dubious since advocates of reform existed before Marx, and he himself was opposed to steady and gradual reforms since he noted that it was akin to hoping that the existing order would "reform itself out of existence".note In the case of America, the New Deal was largely shaped to co-opt class angst and the disrepute of capitalism brought into question by the (then) international and intellectual prestige of Communism (which owed itself to its grounding on Marx's ideas). The American Communists, who were in the margins during The '30s, nonetheless promoted racial equality and organized African Americans in the Deep South during the same period, which ultimately bore fruit in the Civil Rights Movement, which mainstream liberals and some conservatives accepted at last to counter the internationalist appeal of Communism. To quote W.E.B. Du Bois, Marx "put his finger squarely upon our difficulties." Marx himself fluctuated in his attitudes to reform. When the absolute monarchies of Europe started to give way to democracy, he did say that peacefully reforming capitalism was possible in such nations as the United Kingdom and United States, but he argued that such nations as Germany and France had far too deeply entrenched conservative influences for any changes to take root peacefully and argued the same for other nations.note

He actually spent much of his life outside of his homeland. Due to his open, enthusiastic association with all the most radical people of the day, Marx essentially had no chance of ever becoming a professional academic and the Kingdom of Prussia eventually exiled him. He moved to Paris in 1843 and was expelled from France in 1849. From then on, he mostly lived in London. Nevertheless, Marx is still an icon in much of Germany. A nationwide poll in 2003 saw that Germans voted him as the third-greatest German of all time, behind only West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther. To put this in perspective, Marx outpolled all the country's great classical composers, Albert Einstein, and Otto von Bismarck. In fact, arguably the only country where Marx has a net negative reputation is the United States. While some people there, even several of his critics, give him credit for his then-groundbreaking insights, most Americans usually associate him with their old enemy the Soviet Union and the Soviet satellite nations they fought in proxy wars during the Cold War. In any case, by taking the stances that Marx did, he is certain to remain controversial and contentious for future generations and since he never wrote for academic and mainstream respectability in the first place, he might well take heart that his ideas are still countercultural well over a century after his death.

He has no relations to The Marx Brothers, or the final boss from Kirby Super Star. Not to be confused with Karl May, another German Karl M of the 19th century who wrote books that sold by the millions, or with comic book artist Carl Barks. This Karl Marx is also not either of at least two German doctors whose lifetimes partially overlapped his own (one born in 1796![]() , the other in 1857

, the other in 1857![]() ), nor a composer who was born in 1897, after he died

), nor a composer who was born in 1897, after he died![]() . The trope Karl Marx Hates Your Guts is named after him. Also, yes, he kinda does look quite like a grumpy version of Santa Claus, naturally inviting facetious comparisons between his prescriptions for allocating resources and Santa's giving of gifts.

. The trope Karl Marx Hates Your Guts is named after him. Also, yes, he kinda does look quite like a grumpy version of Santa Claus, naturally inviting facetious comparisons between his prescriptions for allocating resources and Santa's giving of gifts.

Many of his writings are in the public domain and any interested person can read them at Marxists Internet Archive![]() .

.

- On the Jewish Question (1843): A response to a fellow philosopher who suggested that the only way Jews could receive political emancipation in much of Europe was to abandon their religion. This work was then seen as a major study of how secular countries actually work, with Marx claiming that even countries without a state religion will see religious forces try to take power. Today, people usually consider it antisemitic, though it should be noted that Marx was himself (ethnically) Jewishnote (he was of course an atheist in terms of actual religious beliefs). May have been intended as a Stealth Parody — the jury is still out.

- Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1844): Not published during his own lifetime. One of his earliest works revealing his communist sympathies.

- The Holy Family (1844): A damning critique of a then-popular group of philosophers known as the Young Hegelians (who, like Marx, were also intellectually influenced by Georg W.F. Hegel).

- The German Ideology (1846): His first collaboration with Engels. A study/critique of what German culture was like at the time. Today valued as the fullest example of his materialist theory of history.

- Wage Labour and Capital (1847): One of his most important studies of how capitalism really works for those on the bottom.

- The Communist Manifesto (1848): Written with Engels. His most famous work. Written in response to the Revolutions of 1848. Needs no description.

- The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852). Essential for understanding the Marxist view of history, it starts with the famous line, "Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce." (Despite much searching, no such remark from Hegel has been found.) He spends much of the essay comparing the coup d'état of Napoleon I on the 18th Brumaire An VIII (9 November 1799) with an 1851 coup by his nephew Napoleon III. It ends with an almost as famous line, "Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past." about Marx's view of the place of the individual in history. In the 20th century, this book gained renewed currency for its analysis about failure in democracy leading to an autocratic-military government with broad popular support with appeals to a romanticized past glory.

- Grundrisse (1858): Unfinished. An examination of a wide variety of topics, namely ones tying to economics. Basically a dry run for Capital, although some Marx scholars hold that there's stuff in this book that Marx left undeveloped.

- Theories of Surplus Value (1863): A very strong critique of the idea that more material creates more wealth. For Marx, it only means more wealth for the wealthy.

- Capital: Critique of Political Economy, also known as Das Kapital (Volume 1, 1867; Volumes 2 and 3 released posthumously). He set out basically to contain all his thoughts about economics and society in these books. Since Marx kept putting off finishing the thing for several years, he died before the second and third volumes were fully completed. Engels edited them after Marx's death and published them. It's massive, so much so that many modern Communist and Marxist movements advise not reading it out of necessity. The hardest parts to understand are the opening chapters of Volume 1, which consist of Marx's abstract theories about labour and value. This is a pity, because many readers never make it to the later chapters, which contain vivid and harrowing accounts of industrial conditions in 19th-century England, with extensive quotations from government reports on the subject.

- The Civil War in France (1871): Notable for being an examination of the famous/infamous Paris Commune of 1871, the most significant socialist revolution within his own lifetime.

- Mathematical Manuscripts of Karl Marx (posthumous): Marx’s writings on infinitesimal calculus, written in 1881 but first published in Russian in 1933, with an English translation arriving in 1983.

- Young Marx (unpublished): A collection of surviving examples of Marx's early works, including fragments of a novel and poetic ventures. Mostly of biographical interest.

Media portrayals:

Period Pieces/Biopic Films:

- 1871 (1990 film), portrayed by Med Hondo (a case of Race Lift).

- The Young Karl Marx (2017 film), portrayed by August Diehl.

- Miss Marx (2020 film), about his daughter Eleanor. Portrayed by Philip Gröning.

Others:

- Assassin's Creed Syndicate as an NPC. He even asks the Fyre siblings to join the Workers' Party but both turned down his offer.

- Monty Python's Flying Circus, played by Terry Jones as one of four contestants (all famous Communists) in World Forum.

- Epic Rap Battles of History, portrayed by Lloyd Ahlquist (opposite Peter Shukoff as Henry Ford).

- The Leader (2019 Chinese web animation series)