When did the first complex multicellular life arise? Most people, being a bit self-centered, would point to the Ediacaran and Cambrian, when the first animal life appeared and then diversified. Yet studies of DNA suggest that fungi may have originated far earlier than animals.

When it comes to a fossil record, however, things are rather sparse. No unambiguous evidence of a fungus appears in fossils until after the Cambrian was over. A few things from earlier may have looked fungus-like, but the evidence was limited to their appearance. It could be that fungi branched off at the time suggested by the DNA but didn't evolve complex, multicellular structures until later. Alternatively, the fossils could be right, and there's something off about the DNA data. Or, finally, it could be that we simply haven't found old enough fossils yet.

A new paper out in today's Nature argues strongly for the last option. In it, a small team of researchers describe fossils of what appear to be fungi that could be up to a billion years old. And the researchers back up the appearance with a chemical analysis.

Really, really old

The fossils come from an area on Canada's northern, Arctic coast. The fossils themselves were discovered by dissolving the minerals that contained them with acid. With the rocks gone, a large collection of small fossils floated free.

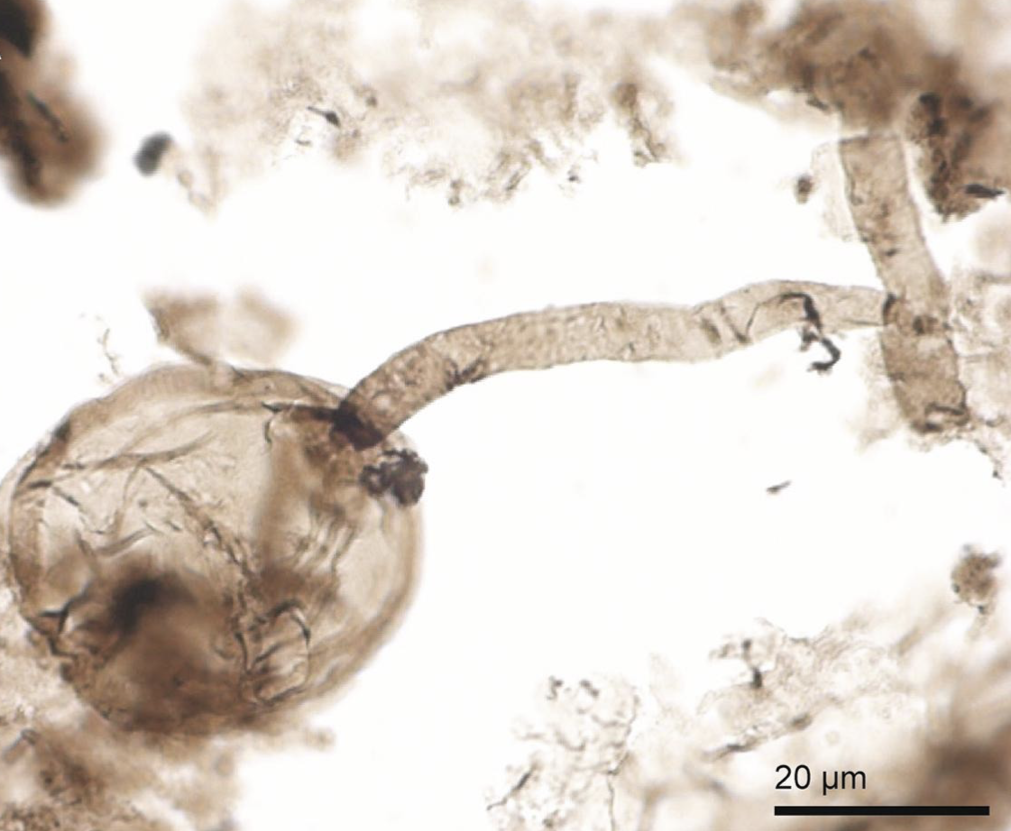

Visually, these microfossils look like a partially deflated balloon with a stalk at its base. Those stalks are connected to a long tube that can link up multiple balloon-like structures. This looks a lot like some modern fungi, where the balloon-like structure is a source of spores while the tubes are how the organism grows and spreads within a surface. One critical feature that's shared with fungi is the fact that the stalk that attaches the sphere to the rest of the organism branches off at a right angle. The structure provided the new genus' name, Ourasphaira, for tail and sphere; the full species name is Ourasphaira giraldae.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...